| If you are unable to view the message below, click here to view |

|

|

D A L I T

H I S T O R Y

M O N T H |

|

|

|

| |

Nausea served in the plate, the untouchable nausea

The disgust grows in the belly, the untouchable disgust

It’s there in the flower buds, it’s there in sweet songs

That a man should drink another man’s blood,

This is the land where this happens

This is the land of hellish nausea.

---From Ek Maitra Raangadya by Sheetal Sathe,

Folk-singer and Dalit rights activist |

| |

I am a venereal sore in the private part of language.

… |

I am broken by the revolt exploding inside me.

There’s no moonlight anywhere;

There’s no water anywhere.

… |

Release me from my infernal identity.

Let me fall in love with these stars.

---‘Cruelty’ by Namdeo Dhasal,

Marathi poet, activist and Dalit Panther |

| |

|

|

|

A poster for Dalit Women’s Self-Respect Yatra by a group called ‘Dalit Women Fight’ in early 2014

Source: Kpfa.org [see below] |

| |

|

|

|

| To this day in India, the Dalit individual continues to be ‘reduced to his immediate identity … To a vote. To a number’ (from Rohith Vemula’s last letter). Caste discrimination and persecution still hunt students in academic spaces, which combined with a lack of context-sensitive pedagogy even in premier institutions of the country, lead to the frequent ‘institutional murder’ of many young, imaginative minds. It has also been observed how the Covid-19 pandemic gave free rein to the ‘educated’ classes to unleash their latent tendencies towards practising untouchability; only this time, it was legitimised under the guise of modern science and hygiene. Dalit workers at crematoriums all over the country who worked tirelessly, undertaking great risks , for over 14 hours every day to tackle the incessant inflow of corpses, during the hellish times of the pandemic were not paid minimum wage in many parts. Manual scavenging continues unabated even in 2023 with more than 500 deaths in the last five years, inspite of legislation banning it. It cannot be denied that unequal opportunities, systemic inequalities and deeply entrenched prejudices continue to plague the everyday life of the Dalit, often denying her dignity, which is the foundation of all fundamental rights. |

| In April, as we celebrate Dalit History Month, we present an eclectic spread of seminal Dalit writings, translated for a wider audience, from rich founts of literature in Marathi, Kannada, Punjabi, Telugu and Bengali. This spread includes imaginative literature, path-breaking Dalit autobiographies, and more perspectives to reinforce the canon and keep it visible and accessible for all who dream of one day living in a world rid of this ‘untouchable…hellish nausea’. We do hope that you will read, share, and recommend these titles to help educate, agitate and organise for a world where all are free of their ‘infernal identity’ and can live in harmony as children of the cosmos, elevated from the muck and contemplating moonlight. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

| |

| The Almond Flowers and Other Stories |

Anil Gharai

Edited by Indranil Acharya

Translated from the original Bangla by Anuradha Sen and Arun Pramanik

With a Foreword by Sayantan Dasgupta |

|

| The Almond Flowers and Other Stories, a collection of thirteen short stories, in translation, is a visceral portrayal of marginalisation and oppression of communities in coastal Bengal, Odisha and the forest kingdom of southwest Bengal. The stories question the development paradigm by focusing on the heart of underdevelopment in a breadth of vision reminiscent of the works of Mahasweta Devi. In these poignant stories, we meet a Banjara girl who refuses to accept the sexual abuse of the women of her community by the police; a poor midwife faced with an opportunity to avenge her husband’s murder by an upper-class landowner; an outcast leper who finds himself shunned at his rich son’s wedding; and in the titular story, an old, decrepit father who, in his struggle to earn a livelihood, unknowingly brings home danger that ruins his young daughter’s hope for a better life. |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

| |

| Poisoned Bread |

| Arjun Dangle (ed.) |

|

| The revolutionary social movement launched by Dr Ambedkar, was paralleled by a wave of writing that exploded in poetry, prose, fiction and autobiography of a raw vigour, maturity, depth and richness of content, and shocking in its exposition of the bitterness of their experiences. Poisoned Bread, first published in 1992, is the first anthology of Dalit writings to be published in English. It is a seminal work featuring works of more than 80 writers, all esteemed names in Marathi Dalit literature, translated from Marathi for a wider readership, and edited by Arjun Dangle, one of the founding members of the Dalit Panthers. One is jolted by the quality of writing of a group denied access to any literary tradition through the ages. This new edition includes an essay by Gail Omvedt (1941–2021), who was a distinguished scholar-activist, working in Maharashtra with new social movements. Omvedt was actively involved in anti-caste campaigns from the 1970s until her passing. |

|

|

|

|

| |

| Shanti Parav: Treatise on Peace |

Des Raj Kali

Translated from the original Punjabi by Neeti Singh |

|

| Written after the great war of Kurukshetra, Shanti Parva, the twelfth book of the Mahabharata, is a treatise on peace, the ideals of statehood and peaceful governance, which also simultaneously justifies upper-caste hegemony, hierarchy and the need for organised violence. Des Raj Kali’s Shanti Parav, in contrast, brilliantly parodies the claims of ‘peace’ of its source text and provides a radical Dalit response from the margins of history to these justifications of the ruling elite. A post-Independence novel set in the heartland of Punjab, Shanti Parav invites a study of post-colonial socio-political dynamics in India from a Punjabi Dalit perspective. The proletarian context of Shanti Parav is harsh and stark, but also colourful, irreverent, carnivalesque, even absurd. Boldly experimental, the novel has a dual narrative which playfully challenges the reader to acquire new ways of reading and interpreting a text. The ‘fictional’ text in the upper half of the page narrates autobiographical stories that recount the struggles and joys of the protagonist’s immediate, everyday subaltern world, while in the lower half run ‘realistic’, quirky, grand historical monologues by three retired Dalit characters who offer philosophical discourses on governance, violence and peace. |

| |

|

| |

| |

|

|

| |

| The Prisons We Broke |

Baby Kamble

Translated from the original Marathi by Maya Pandit |

|

| The first autobiography by a Dalit woman in Marathi Jina Amucha, by Baby Kamble, a veteran of the Dalit movement, was first published in 1986. It redefined autobiographical writing in Marathi, not only in terms of form and narration, but also in the selfhood and subjectivities articulated. It was made available to a wider readership for the first time in 2008 when its translation, The Prisons We Broke was published. This second edition includes translations of Baby Kamble’s Prefaces to the first and second editions of Jina Amucha. Writing on the lives of the Mahars of Maharashtra, Baby Kamble reclaims memory to locate Mahar society before the impact of Babasaheb Ambedkar. The Prisons We Broke is a graphic revelation of the inner world of Mahars, and the oppressive caste and patriarchal tenets of Indian society. Kamble vividly and unapologetically brings to life the rituals and superstitions, the joys and sorrows, the hard lives and the hardier women of the Maharwada. Breaking the bounds of personal narrative, it is at once a sociological treatise, a historical and political record, a feminist critique, a protest against brahminical Hinduism, and the memoir of a cursed people. |

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

| Government Brahmana |

Aravind Malagatti

Translated from the Kannada by Dharani Devi Malagatti, Janet Vucinich and N. Subramanya |

|

| Aravind Malagatti’s Government Brahmana is the English translation of the first Dalit autobiography published in Kannada. The autobiographical narrative is in the form of a series of episodes from the author’s childhood and youth. These episodes function as what G.N. Devy calls ‘epiphanic moments’ in a caste society. The author reflects on specific instances from his childhood and student days that illustrate the normative cruelty practised by caste Hindu society on Dalits. We encounter all the tropes of (male) Dalit life: isolation in school where even drinking water is an ordeal; life in the village where Dalits perform the filthiest tasks but are denied access to common wells, lakes; where they cannot step into shops and therefore have their purchases thrown at them; where they have to cut their own hair because no barber would touch it; consuming dead-animal meat and innards; doomed love affairs with `upper’ caste women. In its structure and purpose – as a series of notes towards a Dalit autobiography – Government Brahmana appears to be anticipated by Ambedkar’s own autobiographical sketches. Government Brahmana has received the Karnataka Sahitya Academy Award. |

| |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

| |

| Sorajjem |

Akkineni Kutumbarao

Translated from the original Telugu by Alladi Uma and M. Sridhar |

|

| Written in 1973 and published in 1981, Sorajjem is one of the early Telugu novels written by a non-Dalit writer that depicts the problems faced by the Dalits. This masterful translation captures the lived reality of inhumanity, alienation, displacement and sexual atrocity that the Dalits face at the hands of caste-Hindus, and explores why seeds of revolution are sown in Dalit lives. In Malapalli, an ‘Untouchable’ corner of a village in the Andhra region, every child’s dreams are crushed. They cannot stay at school. They tend the buffaloes. They work the fields. They are sexually exploited. They are expected to be content with a paltry pay. When they assert their rights, they are threatened, killed, or worse, forced to migrate to unknown far-away lands. This is the story of the first sixteen years in the life of Sorajjem, born during the month of India’s Independence. It is also a story of the sufferings of her community, the Malas. This story is set in the recent past. But it can well be a story of contemporary India. |

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

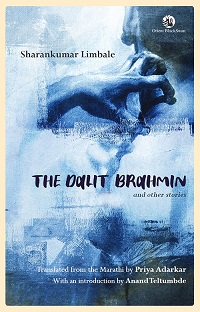

| The Dalit Brahmin and Other Stories |

Sharankumar Limbale

Translated from the original Marathi by Priya Adarkar

With an introduction by Anand Teltumbde |

|

| Sharankumar Limbale’s stories open up a brutal and cruel world conditioned and sanctioned by the caste system. They present an account of Dalit lives in post-independence India, with the Ambedkarite movement, and the schisms within it, as a prominent backdrop. The anti-Dalit logic of reserved constituencies, the predicament of Dalit writing, the fallout of communal violence for those at the margins, the implications of festivals like Ganapati, the contradictions of job reservations, the horrors of the institution of schooling; family, childhood, friendships, love, sexuality—all take on dark new hues. They are also a rare and moving account of Dalit masculinity today. ‘Dalit Brahmin’ is a sarcastic epithet for the urban, educated Dalit middle class who look down upon their own folk much as the brahmins do, and seek to distance themselves from their caste identity. Yet, it is also this class which bears the responsibility of emancipating the Dalit masses from the chains of caste. Unsettling and exuding a stark raw power, these vibrant cameos—seamlessly translated by Priya Adarkar—comfortably bridge the difficult divides between imaginative literature, autobiographical fiction and documentary narrative. |

| |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

| |

| |

| |

|

| |

Keep in touch

Facebook at www.facebook.com/OrientBlackSwan

LinkedIn at www.linkedin.com/company/orientblackswan

Twitter@OrientBlackSwan |

Place an Order

info@orientblackswan.com |

| |

|